Introduction: A Personal Encounter with a Ghost Teacher

I first heard the story in Paris, over coffee with an old friend. She spoke of a mysterious online language teacher who had enchanted her cousin’s family. For years, a tutor claiming ties to a prestigious Moscow university held weekly Skype sessions from abroad, providing instruction in Russian and Chinese to the Legrand family. Over time, he became more than a language teacher – a seemingly benevolent and trustworthy figure who remembered birthdays, gave life advice, and inserted himself into the intimate fabric of the family's daily life. The interaction was peppered with references to well-known personalities, espionage-themed anecdotes, and increasingly strange Mata Hari-like stories, often containing unnecessary sexual details and recurring homosexual undertones. The tutor repeatedly described himself as a victim of persecution in Russia due to his sexual orientation, a narrative which, in the context of widespread LGBTQ+ repression in Russia, was neither shocking nor suspect to the family, living in France.

Despite growing familiarity, he never once turned on his camera, always citing reasons such as “Asperger’s syndrome” or privacy issues. He also systematically refused to meet in person, even when he was supposedly nearby. His personal stories were vague, as if delivered from a script – polished, yet hollow.

Later, when the "teacher" learned about a minor medical issue in the family, he offered to help. He claimed to know a skilled doctor in Turkey who could offer fast, affordable treatment. He even proposed to cover the travel cost using personal discounts, but required scanned copies of their passports. He later claimed to have bought the tickets through a Turkish friend and provided the travel details. At the airport, however, it turned out that no tickets had been purchased. The family briefly considered buying new ones themselves, puzzled by the inexplicable "mix-up." As they stood deliberating, a passerby mentioned something cryptic – that the flight was “a disaster.” Taking it as an ominous coincidence, they decided not to go.

That decision may have prevented an irreversible mistake. But they did not cut off contact with the tutor, only assuming it had been an unfortunate mistake. Soon after, an opportunity arose to purchase a parking lot. The price was attractive but they were short a portion of the funds. When they mentioned this, the tutor eagerly offered to help, promising to cover the missing sum. They were hesitant, but agreed. The closing date approached, and they urgently needed to place a deposit. When they asked the tutor to wire the funds, he claimed to encounter technical issues. Then, he offered an alternative – the money would be delivered in cash, by a man coming from Madrid. The man, he added casually, was Iranian. This already strange arrangement crossed a line.

Alarmed, the family began to examine the tutor’s digital presence more closely. What they found defied belief. Social media accounts once taken at face value revealed inconsistencies, connections to obscure individuals with identical writing styles, and ultimately, signs of artificial fabrication. From that moment, it became clear: they were not dealing with an eccentric friend – but with a meticulously constructed, multi-layered operation. The photos were AI-generated; the voice on calls sometimes glitched. When confronted, the persona vanished, leaving the family bewildered and betrayed. For me, as a graduate of MGIMO – Russia’s elite diplomatic academy – the revelation was chilling. The tactics were familiar. I had studied such methods of persuasion and deception in school as a part of "ideological borba"- ideological war methods. Now I was seeing them weaponized in real life. This Parisian family’s emotional bond with a fictitious mentor was not a random catfishing incident; it bore the hallmarks of an engineered influence operation. It was a modern incarnation of what we might call “narrative bonding” – forging trust through personal storylines – taken to an extreme. In retrospect, it felt as if a piece of cognitive malware had been implanted in their lives, an insidious program of influence running quietly in the background.

I left that conversation unsettled, stunned how a ghost teacher could so effectively embed himself in a family’s trust. The answer, I suspected, lay in the advanced rhetorical strategies and psychological tactics that I had seen emphasized at MGIMO. Over decades, MGIMO has honed the art of strategic communication – teaching future diplomats and intelligence officers how to wield language as a weapon. Now, those tactics seemed to have evolved beyond traditional propaganda broadcasts, into something far more intimate and controlling. I decided to trace this deception back to its source, dissecting how such a scheme could be constructed and to what end.

MGIMO and the Art of Rhetorical Manipulation

Founded during the Soviet era, MGIMO (Moscow State Institute of International Relations) has long been the forge for Russia’s diplomatic and intelligence elites. Often described as “the symbolic sword of Russian international discourse”, MGIMO arms its graduates with linguistic prowess, diplomatic savvy, and a deep toolbox of influence techniques. It operates under the Foreign Ministry, blending academia with statecraft. In essence, MGIMO is both an academic institution and an incubator of state rhetoric and strategic influence skills. Graduates commonly ascend to key positions in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, intelligence agencies, state media, and policy think tanks, acting as carriers of Kremlin narratives worldwide. In the Cold War, this meant mastering propaganda and “active measures” for ideological battles. But in the 21st century, MGIMO’s curriculum has expanded beyond old-school propaganda. Students delve into rhetoric, pragmatics, psychology, and information warfare, studying how to craft messages that bypass rational defenses and tap into emotions and context.

One concept we explored in my MGIMO courses was the idea of “reflexive control” – a Soviet theory of influencing an adversary’s decisions by shaping their perceptions. The modern Russian approach to influence builds on this principle: get targets to act in the interests of the propagandist without realizing it. Unlike blunt lies or obvious agitprop, these techniques favor obfuscation, context manipulation, and subtle persuasion. The MGIMO playbook emphasizes reading the target’s psyche and tailoring messages to it – essentially hacking the human cognitive system. In the old days, propaganda was often a sledgehammer of ideology; MGIMO teaches how to use a scalpel. Rhetorical strategy at MGIMO isn’t just about winning debates – it’s about constructing entire realities for the audience, through carefully engineered narratives.

A striking part of MGIMO’s rhetorical arsenal is what I call “contextual camouflage”. This means crafting personas and stories that blend so seamlessly into the target’s worldview that the persuasive intent is hidden. The “language teacher” persona in Paris was a textbook example: offering genuine language skills and friendly mentorship – valuable services – while gradually seeding pro-Russian talking points and gaining influence over the family’s opinions. By the time suspicion arose, the persona had already woven itself into their emotional fabric. This goes beyond any propaganda technique I learned about in history books. It represents a new breed of influence operation, one that fosters a bond before delivering a message.

MGIMO’s pedigree in language and cultural studies also enables these tactics. Students learn multiple languages and study abroad, grooming them to impersonate many identities. They practice storytelling, negotiation, and even improvisational acting – skills useful for creating credible personas. The institute’s emphasis on pragmatics (the influence of context on meaning) and discourse analysis trains graduates to shape narratives that “fit” the audience’s context. In the AI era, MGIMO scholars like Professor Elina Kolesnikova highlight the importance of rhetorical analysis to understand why a text persuades in a given situation. All of this academic theory has a dark twin in practice: weaponized narrative control.

Beyond Propaganda: Narrative Bonding as Cognitive Malware

Traditional propaganda – whether Soviet, Nazi, or classic wartime American – was largely mass-oriented and overt. It used posters, radio broadcasts, speeches and newspapers to push an ideology or boost morale. Today’s tactics, as evidenced by the Paris case, are far more personal and covert. Instead of blasting a single message to millions, an operator can carefully bond with one target at a time through a bespoke narrative. Think of it as malware for the mind. Just as malicious software infiltrates a computer by disguising itself as legitimate, these narrative tactics infiltrate a person’s mind by posing as a legitimate relationship or source of information. Once inside, they can execute a “payload” – influencing beliefs or behavior – all while the target remains unaware of the manipulation.

The analogy is not just poetic; experts in information warfare are literally using terms like cognitive malware. In fact, researchers describe cognitive malware as analogous to cyber malware: “highly distributed, originating from a variety of state and private actors, and seeking to disorient its targets”[1]. Instead of crashing your hard drive, cognitive malware disrupts logical reasoning and implants false or biased narratives. Narrative bonding is a prime delivery mechanism for this malware. By emotionally hooking a target through a compelling personal story or relationship, the operator can slip in disinformation or extremist ideas under the radar of skepticism. The target, bonded by trust and emotion, will often accept these ideas or even act on them, believing them to be self-chosen conclusions.

In our Paris case, the behavioral control structure implanted was subtle. The family slowly adopted the “teacher’s” rosy view of Russia and its culture. He would mention in passing how Western media “misunderstands” Russia, or how certain Russian policies were sensible. Over time, these narratives took hold. The family began echoing those talking points in discussions, not realizing they had been gently indoctrinated. This is how behavioral influence can be seeded: no one is ordering the target to change their stance; instead, the narrative bond nudges them toward the desired mindset until they steer themselves accordingly. The ultimate victory for a propagandist is exactly that: the target thinks it was their own idea. Contemporary Russian influence operations explicitly aim for this outcome – to “engage in obfuscation, confusion, and the disruption or diminution of truthful reporting” such that the audience is overwhelmed and manipulable.

Crucially, these modern tactics leverage emotional resonance. Psychological research shows people are often more moved by stories and relationships than by facts or logic. A fabricated persona can exploit this by playing the role of a sympathetic friend or mentor. We’re seeing a shift from propaganda as a blunt instrument of ideology to propaganda as a “friend in your feed” – a fake friend, that is. This friend shares memes, personal messages, life advice, etc., along with carefully targeted political content. It’s propaganda wearing the mask of companionship.

The MGIMO-informed strategist recognizes that narrative and emotion form the backdoor to the human mind. While an outright false headline might trigger skepticism, a personal narrative disarms the critical faculties. In cybersecurity terms, it’s social engineering: why hack the system when you can convince the user to open the door for you? Narrative bonding creates compliance through trust. Once trust is established, the “payload” can range from subtle influence (shaping opinions) to direct action (like recruiting someone to pass information or support a cause). The victim often cannot pinpoint when their autonomy was subverted – a hallmark of effective cognitive malware.

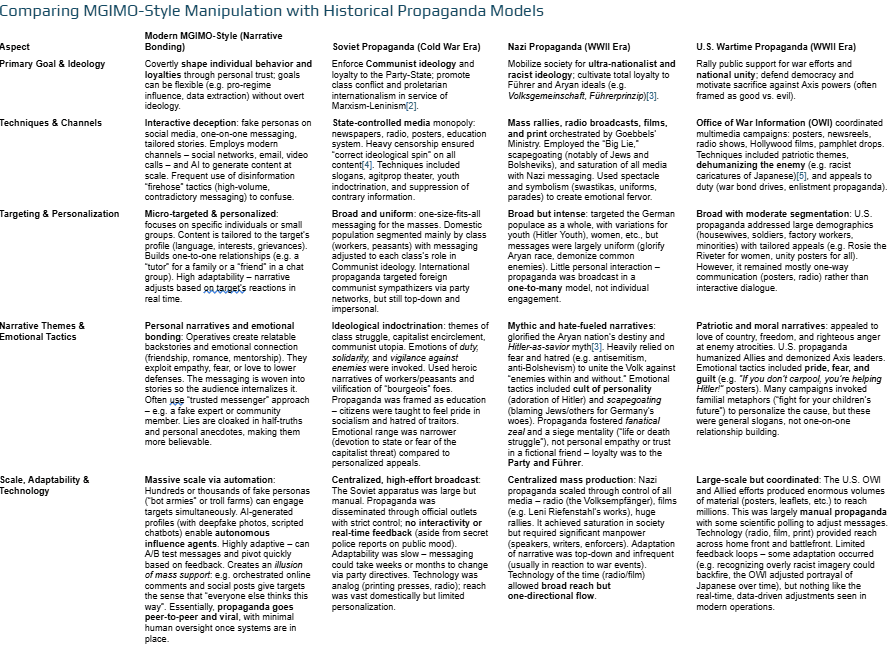

To better understand how groundbreaking these tactics are, it’s useful to compare them side-by-side with historical propaganda models. Below is a comparison of MGIMO-style narrative manipulation versus classic propaganda approaches of the past:

Table: Side-by-side comparison of modern MGIMO-influenced rhetorical manipulation vs. historical propaganda models. We see that modern tactics are more personalized, interactive, and technologically powered, focusing on deep psychological infiltration rather than overt mass messaging. Link to the table https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vTz323axKCiu0-msLFxRSCp5_dGmihrPMEJS0VDETtavv5e-fgvReuIWOqK_ePCqw5V4nE61AmRd9bz/pub

AI-Based Psychological Infiltration: The Next Frontier

Looking forward, the implications of these modern tactics are amplified by advances in artificial intelligence. In the Paris case, at least some aspects of the “teacher” persona appeared to use AI – possibly an AI-generated profile photo or even AI-assisted chat responses. We are entering an era where autonomous agents can simulate human connection on a grand scale, for malicious ends.

Imagine dozens of “ghost teachers,” “friendly advisors,” or even “romantic interests” all crafted by a hostile actor but powered by AI to be responsive and engaging. Unlike a human operative who has limited time and can handle only a few relationships, an AI-driven persona can simultaneously manage thousands of conversations, 24/7, without fatigue. And thanks to machine learning on big data, these agents can be uncannily good at emotional manipulation – adjusting their tone and content to each target’s psychology. This is not science fiction; early versions are already observable. In June 2023, for example, Russia’s LDPR party unveiled an AI chatbot of their deceased leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky, allowing the ultranationalist firebrand to “speak” again and spout propaganda in his own voice[6][7]. Trained on 18,000 hours of his speeches, the virtual Zhirinovsky confidently declared that Ukraine was a “swamp of traitors and Russophobes” and predicted Russian victory – demonstrating how an artificial persona can carry forward a narrative beyond the grave. This was a high-profile demo; more surreptitious uses of similar technology are likely under development.

Beyond resurrecting known figures, AI can create entirely fictitious personas with full legends (backstories). We have seen intelligence warnings about fake profiles on professional networks: the case of “Katie Jones,” a nonexistent redhead with an AI-generated face who networked on LinkedIn with Washington, D.C. insiders, is a prime example[8]. The Associated Press found that Katie Jones was part of a “vast army of phantom profiles” used to spy or influence, with experts confirming her profile photo was a deepfake[8]. That was in 2019. Since then, AI capabilities have exploded. It’s now trivially easy to generate realistic photos (through GANs), mimic voices, and deploy chatbots that can hold convincing conversations.

Autonomous influence agents could be deployed as “force multipliers” for psychological operations. A single handler might supervise a fleet of AI personas targeting different communities – for instance, one persona infiltrates a dissident group’s chat by pretending to be a like-minded activist, while another befriends military personnel on social media, and yet another poses as a dating prospect on a apps frequented by government staff. Each agent gathers intelligence and nudges targets in line with the operator’s goals (from sowing distrust in institutions to eliciting specific actions). Because these agents can be partly or fully automated, they dramatically lower the cost and risk of traditional human intelligence or influence operations. It’s the scalable weaponization of trust.

We are also likely to see AI being used for refining rhetoric. Just as Large Language Models can be used to draft persuasive text, they can help propagandists iterate and optimize their narratives. An AI could generate hundreds of variant messages or social posts and test which ones get the most engagement or trigger the desired emotion. This is propaganda entering a Darwinian auto-evolution loop – only the most effective memetic “mutations” survive and spread. Couple this with deepfakes in video and audio, and one can orchestrate entire illusionary communities of personas: an army of AI-generated people all voicing agreement, to create a false consensus effect. Indeed, Russian influence operations already leverage a “firehose of falsehood” approach with numerous channels and contradictory messages to overwhelm audiences. AI will turbocharge this – bots that argue both sides of an issue, confuse observers, and make truth-seeking exhausting.

Another development is AI-curated echo chambers. Algorithms already personalize content feeds to our tastes; a malicious actor can use that to gradually steer a target down a specific rabbit hole. Over time, the content an AI persona shares with you can shift from benign to extreme in a process akin to radicalization. Because the persona has built a bond, the target follows along the narrative arc – a slow boil that’s hard to notice. In effect, AI will enable finely tuned, behavioral control structures that adapt to each individual’s responses. This is psychological infiltration at scale and in depth.

From a defensive standpoint, this is deeply worrying. Intelligence and law enforcement professionals must anticipate autonomous propaganda: fake journalists writing articles, AI news anchors delivering tailored disinformation (already seen in pro-Kremlin “news” deepfakes), or chatbots posing as concerned citizens in civic discussion forums. The line between human and machine influence operations is blurring. We will likely confront scenarios where an adversary doesn’t just influence the information environment but populates it with illusionary actors who shape human behavior en masse.

The future might see something like an “AI spy companion”: an AI agent that latches onto a target for months or years, guiding their opinions, feeding them tailored propaganda, perhaps even encouraging them to make choices (voting, activism, leaking info) that serve a foreign agenda – all under the guise of a genuine friend or mentor. It’s the logical (and terrifying) extension of the narrative bonding we saw in Paris, now supercharged by automation and data-driven precision.

Detection and Defense: Tools for OSINT and HUMINT Operators

Confronted with these evolving threats, investigators and intelligence analysts need to augment their toolkits. Detecting a sophisticated narrative infiltration is not easy – by design, these operations hide in the noise of genuine social connections. However, there are emerging methods and best practices to counter them. Below, I outline some prompt templates and fact-checking techniques that OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) and HUMINT (Human Intelligence) professionals can use to identify and disrupt narrative manipulation:

- Digital Persona Verification: When encountering a suspicious online persona, perform a reverse image search on their profile photos. Many AI-generated faces can be spotted with tools that detect anomalies (e.g., symmetric features or odd artifacts). If the photo appears nowhere else on the internet except that profile – a red flag. Also, use video frame analysis** if they appear in videos; deepfakes sometimes have inconsistent eye blinking or lighting issues.

- Cross-Check Background Details: OSINT researchers should cross-verify any biographical details the persona provides. For example, if “Dr. John Smith” claims a degree from X University or a job at Y Company, check alumni lists, staff directories or LinkedIn for corroboration. In the Katie Jones case, a simple call to the think tank she claimed to work at revealed no such employee[9]. Discrepancies in timeline or education history are indicators of a concocted identity.

- Conversation Analysis via AI: Ironically, we can fight AI with AI. One can deploy language model-based tools to analyze communications for hallmarks of manipulation. For instance, an analyst could use a prompt like: “Analyze the following chat logs. Identify any persuasive or rhetorical techniques, emotional appeals, or inconsistencies that suggest one party might be a fictitious persona or engaging in influence tactics.” The AI might highlight overly flattering language, unusually fast intimacy, mirroring of the target’s opinions – all potential signs of social engineering. Prompt templates for this purpose can be shared in OSINT communities to standardize the practice. (It’s crucial, however, to fact-check the AI’s output – it can suggest leads, but a human must verify.)

- Behavioral Red Teaming: HUMINT operators can actively test a suspicious persona. For example, introduce deliberate false information in conversation and see if it gets parroted back later (indicating the persona might not have an independent life outside the interaction). Or subtly challenge them with a request that a real person would typically refuse (like a spontaneous video call at an odd hour) – many bots or operatives will evade such traps. If an online “friend” consistently avoids live interaction or has a flimsy excuse for every missed meeting, one should probe further.

- Monitor for Coordination: Often, what appears to be one friendly contact could be part of a larger coordinated effort. OSINT analysts should watch for networks of personas. Do multiple new “friends” on a forum all advocate the same viewpoint using similar phrasing? Are they amplifying each other’s posts? Using network analysis tools on social media data can reveal clusters of accounts that behave like botnets or troll farms – for instance, accounts that were created around the same time, have overlapping follower lists, or post in a synchronized manner. Such coordination signals an operation, not organic behavior.

- Critical Narrative Evaluation: Analysts and journalists should be trained in rhetorical analysis. This means not just fact-checking what is said, but how it’s said. Identify emotional triggers or frames. A sudden narrative that “everyone else is against you except me” is a classic isolation technique. Propagandists often use loaded language and false dichotomies. Having a mental (or printed) checklist of common manipulation tactics (appeals to fear, bandwagon claims, discrediting of contrary sources as biased, etc.) can help operators spot when a conversation stops being normal and starts looking like recruitment or indoctrination. For instance, ask: Is this person mirroring all my beliefs to gain my trust? Are they unusually knowledgeable about me (perhaps via prior reconnaissance)? Do they deflect when I ask personal questions? These are signs of a potential dangle.

- Prompting for Transparency: If using AI as a co-analyst, one can craft prompts to get a second opinion on content. A useful prompt template might be: “You are an OSINT analyst assistant. You will be given a social media post or conversation. Your task: determine if the language and behavior align with known propaganda or influence techniques (such as flattery, fearmongering, unverifiable claims, excessive posting frequency). List any red flags you detect.” By running suspect content through such a prompt, an investigator can get a quick rhetorical triage. Recent studies have noted that being able to recognize typical rhetorical tricks and false narratives (emotional manipulation, fear appeals, fake authority) is key to countering influence[10].

- Humint Liaison & Interrogation: In cases where a human source may have been approached by a fake persona (e.g. a government employee who was chatted up by “an analyst from a think tank”), debriefing that source with targeted questions is vital. Train personnel to preserve chat logs and not just delete them out of embarrassment. Skilled interviewers can then go through the logs and ask the human target: “When did you first feel something was off?”; “What did they ask you to do or believe?” Such questions both gather intel on the techniques used and help the target process the manipulation (reducing the lingering psychological grip of the narrative).

- Public Awareness & Education: On a broader scale, strengthening society’s immunity to cognitive malware is akin to cybersecurity awareness training. Intelligence agencies are working with partners to promote media literacy and critical thinking. Simple practices like the “Three Questions” method can be taught widely: “Who said this? What’s their goal? How can I verify this?”. These prompt people to consider the source and motive behind information, which can foil many basic influence attempts. Likewise, encouraging a habit of verifying sensational claims through trusted fact-checkers or multiple sources can help prevent the “emotion rush” that malware relies on.

From an organizational perspective, counter-influence teams are establishing what we might call “cognitive firewalls.” Just as IT security sets up firewalls to catch malicious code, these units use a combination of AI filters, human analysts, and tip lines to catch malicious narratives. For example, some social media platforms now label or remove deepfake profiles when found. Intelligence services share information on new tactics observed (e.g. a recent campaign using AI-generated voice messages to phish officials). International cooperation is also key: alliances like the EU vs Disinfo initiative, and emerging norms around disinformation as a security threat, help coordinate responses. Yet, given the scale of the challenge, our defenses will inevitably miss some attacks. Therefore, resilience is crucial – an informed public and vigilant professional community can limit the damage even when infiltration occurs, by quickly exposing the deception and neutralizing its influence.

Conclusion: Balancing Narrative and Vigilance

The Paris incident with the ghost teacher brought home to me that the front lines of information warfare have moved inside our personal relationships. A friendly voice on a video call, a helpful stranger in a forum, a charismatic mentor online – any of these could be the tip of an iceberg of state-crafted manipulation. As an intelligence analyst, it’s a sobering realization that rhetorical tactics I once studied in theory are now operational in the wild. The evolution from propaganda posters to AI personas is as dramatic as the leap from muskets to cyberwar. Yet, knowledge is power. By understanding how these narrative bonding techniques operate like cognitive malware, we can better inoculate ourselves and our societies against them.

For intelligence and law enforcement professionals, this means expanding the mindset. The threat is no longer just foreign broadcasts or hackers stealing data; it’s an insidious form of human hacking – the weaponization of the trust we naturally extend to others. We must treat unusual influence attempts with the same alertness we would a network intrusion. The tradecraft of counterintelligence must adapt: background checks now include analyzing an official’s social media contacts; counter-influence drills become as standard as phishing drills in agencies.

Investigative journalists, too, play a role. Many recent influence operations have been unmasked by journalists who noticed something “off” in online interactions and dug deeper. By sharing these stories (as I am doing here) and citing concrete cases, we raise awareness. The more case studies we examine – from Cold War “Romeo spies” who seduced targets over years[11] to 21st-century deepfake LinkedIn profiles – the better we get at recognizing the patterns. History, in a way, is repeating itself with new tools. The Stasi’s “romeo” agent who spent seven years wooing a secretary to steal NATO secrets[12][11] is an analog precursor to the digital “loverboy” bots that might seduce sources tomorrow. The common thread is exploiting human emotion, and that hasn’t changed.

A recent cultural reflection of these dynamics appears in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023), which, beyond chronicling the development of the atomic bomb, touches on the infiltration of the Manhattan Project by Soviet agents. Klaus Fuchs, a physicist who leaked critical information to the USSR, is depicted in the film, representing the subtle, long-game infiltration tactics of the era. Equally emblematic is the case of Julius Rosenberg, who, along with his wife Ethel, passed atomic secrets to the Soviets and was ultimately executed. These historical examples show that seemingly loyal, integrated individuals can serve as conduits for foreign powers. The same logic applies today. Only now, the tools have changed. Psychological proximity, narrative manipulation, and virtual personas have replaced spy rings and dead drops, but the aim remains the same: to exploit trust, harvest intelligence, and destabilize from within.

Another chilling parallel arises from the still unfolding revelations surrounding Jeffrey Epstein. While public discourse often reduces the case to a grotesque tale of pedophilia, the scale, reach, and structure of Epstein’s network point to something far more strategic. The Epstein files suggest not merely the exploitation of underage victims but a deliberate and systematic attempt to compromise financial, political, and scientific elites in the United States. Connections to Russian individuals and intelligence-linked intermediaries raise credible suspicion that parts of Epstein’s operation functioned as a covert influence campaign, aimed at overturning democratic norms, gaining access to trade, intelligence, and technological secrets, and channeling control toward authoritarian-aligned actors.

The billions of dollars that passed through his accounts, the inexplicable protection from serious prosecution for decades, and his sustained relationships with figures at the highest levels of power, including a long-standing and personal connection to the current President of the United States, cannot be dismissed as coincidental. They reflect a broader systemic vulnerability: when elite access, sexual blackmail, and foreign intelligence objectives converge, the result is not just a criminal conspiracy but a national security breach with geopolitical consequences.

This redefinition of espionage and subversion as deeply personal, embedded within digital intimacy, collapses the boundary between historical spycraft and the present era of algorithmic infiltration. From Rosenberg’s betrayal inside the Manhattan Project to Epstein’s blackmail architecture targeting the elite, the terrain of conflict has shifted from secure bunkers and foreign embassies to encrypted chats and virtual personas. In this new theater, trust itself is the weapon. AI-generated identities, voice clones, and emotional simulation models open terrifying new vectors, not only for data theft but for full-spectrum psychological occupation. These cases are no longer just cautionary tales from history; they are blueprints. The core tactic endures: seduce, embed, extract. With AI’s accelerating capabilities, the scale and subtlety of this manipulation threatens to outpace human detection. Infiltration now comes with a friendly voice, a deepfake smile, and a perfectly timed message.

However, one forward-looking implication gives a sliver of hope: the same AI technology enabling these threats can help counter them. We are already seeing AI that can detect deepfakes, algorithms that flag coordinated inauthentic behavior, and language models that assist in analyzing suspicious content. It will be an arms race – sword versus shield – between propagandists and defenders. But if we foster collaboration between tech experts, psychologists, and intelligence professionals, we improve our odds of building effective cognitive defenses.

In the end, staying ahead in this domain requires a blend of personal vigilance and systemic innovation. My journey from MGIMO’s lecture halls to the cafés of Paris taught me that stories can be as dangerous as any weapon, and that those who craft and spread them deliberately are the new combatants in a shadow war for hearts and minds. Our task is to shine light on those shadows. We must continue to balance narrative with truth, emotional resonance with factual rigor. By doing so, we affirm that while our enemies may abuse the power of stories, we can still harness stories to educate, warn, and ultimately protect.

In the war of autonomous agents and psychological infiltration, an informed and alert society is our best firewall. The ghost teachers and phantom friends thrive on ignorance and trust. By understanding their playbook – much of it traced back to places like MGIMO – we take the first step in reclaiming our cognitive sovereignty. The next time a “too-good-to-be-true” persona enters our lives or networks, we will be ready to challenge the narrative, fact-check the claims, and, if needed, call it out for what it is: an enemy with a friendly face.

* * *

- Kolesnikova, E. V. – Discussion on rhetoric’s role in AI-era influence.

- RAND Corporation – Russia’s “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model (Paul & Matthews, 2016).

- MGIMO analysis – MGIMO as a symbolic “sword” of Russian discourse.

- Wikipedia – Propaganda in Nazi Germany (ideology and themes)[3].

- Wikipedia – Propaganda in the Soviet Union (censorship and indoctrination)[4][13].

- Wikipedia – Propaganda in World War II (U.S. wartime propaganda goals and tactics)[14][5].

- The Guardian – “The spy who loved her” (Cold War Stasi “Romeo” spy case)[12][11].

- The Moscow Times – Far-Right Party Unveils AI Chatbot of Zhirinovsky (AI persona propaganda)[7].

- Associated Press – “Katie Jones” LinkedIn deepfake spy profile exposé[8].

- Atlantic Council / DFRLab – Research on detecting propaganda narratives (recommendations for critical questioning).

Citations:

[1] cj2021.northeastern.edu

[3] Propaganda in Nazi Germany - Wikipedia

[10] Intentionally deleted